Quileute Territory (From: Forks -- Thumbnail History - HistoryLink.org)

The Quileute Indians once occupied lands throughout the interior West End, including the area of Forks. Their territory stretched north from La Push at the mouth of the Quillayute River (the tribe and river spellings differ) to adjoin Ozette and Makah lands, then east to the headwaters of the Soleduck and Hoh rivers, and south to the Quinault River.

The Quileutes thought themselves wronged by the 1855 and 1856 treaties that ceded their territory, not realizing they had signed away their traditional lands. A reservation was eventually created around the village of La Push in 1889, the same year Washington became a state. And though the remote area experienced little early pressure from white settlement, in 1889, settler Daniel Pullen burned down the entire village while the villagers were picking hops in Puget Sound. They returned to find nothing of their longhouses, tools, artwork, or ceremonial items. This was an episode in a land dispute later decided in favor of the Quileutes,

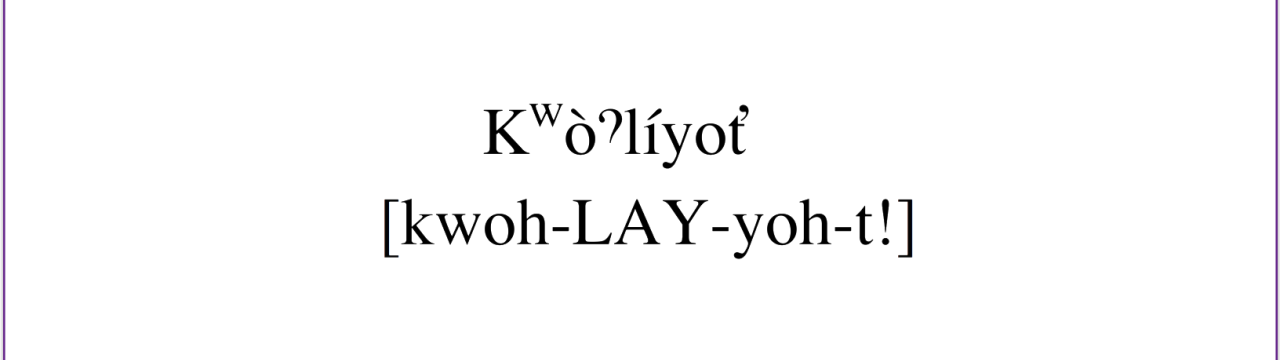

Forks sits 12 miles inland from La Push on a prairie one mile wide and three miles long that was regularly burned by area tribes to regenerate young fern fronds eaten by elk and deer, which the Indians hunted. Two names for Forks Prairie in the Quileute language -- the only surviving language of its kind -- both mean "prairie upstream," and the open area is bounded by the Bogachiel River to the south (from bokachi'l, "muddy water") and the Calawah River to the north (from kalo'wa, "in the middle") (Powell and Jensen, 62-67). Settlers called it Indian Prairie or Big Prairie.

Cultural Context (from: https://centurywest.com/quillayute-amp/)

It is important to note that many of the name designations applied to past peoples (particularly during contact and early historic periods), are those given by European explorers, Euro-American settlers, and others compiling information for treaty purposes.

Puget Lowland archaeology can be subdivided into three time periods: the early (10,500 to 5,000 years BP), middle (5,000 to 1,000 BP) and late periods (1,000 to 250 BP).

The early period is characterized by activities to support habitation within camps along river terraces or outwash channels. Tool technology is primarily characterized by the use of flaked stone tools including fluted projectile points, leaf-shaped points, and cobble-derived tools. These artifacts are often attributed to the “Olcott” phase, named after the site-type near Arlington and Granite Falls (Baldwin 2008; Kidd 1964; Mattson 1985). Suggested by Mattson (1985:83) and Kidd (1964:26), Olcott sites are generally located away from modern shorelines, where occupation took place along terraces of active water courses of the time. Today, these past habitation areas are often found away from modern rivers, as the course of waterways and channels have shifted over time. Besides the lithic assemblage, little faunal or organic evidence dates to this period - likely a result of poor preservation due to the soil composition and elapsed time. The lack of organic evidence and the abundance of lithic materials unintentionally skew the archaeological record to suggest a specialization of terrestrial hunting practices.

The middle period coincides with a stabilization of the physical environment and climate to modern conditions. The middle period is noted for its increased artifact and trait diversity including a full woodworking toolkit comprised of bone and antler implements, art and ornamental objects, status differentiation in burials, and extremely specialized fishing and sea-mammal hunting technologies (Ames and Maschner 1999; Matson and Coupland 1995; Moss 2011; Wessen 1990). Lithic technology becomes specialized to include smaller notched points and ground stone (Moss 2011; Nelson 1990; Wessen 1990). Shell midden sites first appear during this period, indicating a transition to a predominantly maritime-based subsistence pattern (Matson and Coupland 1995; Nelson 1990; Thompson 1978). Although structural elements such as post molds have been identified (Moss 2011; Nelson 1990), habitation structures have not been excavated.

The late period is dominated by a settlement pattern along the coastline, streams, and rivers that show evidence of increased fortification (Ames and Maschner 1999; Matson and Coupland 1995; Moss 2011). Rising sea levels and riparian environments supporting large salmon runs allowed salmon to become a predominant food source (Moss 2011; Wessen 1990). The late period is generally recognized by an apparent decrease in artifact diversity. Stone carving and chipped stone technologies nearly disappear, while trade goods (indicating extensive trade networks along the coast and with inland plateau peoples), increase (Moss 2011; Nelson 1990; Thompson 1978).

Ethnographic

The Quillayute Prairie and surrounding land are within the traditional territory of the Quileute Indian (Pettitt 1945). Quileute native culture is the southernmost representative of the Northwest Coast cultural complex. Many Quileute cultural traits were shared with their neighbors, including the Makah in the north and Quinault to the south. At the time the first white men arrived, Quillayute tribal organization included a number of settlements within their territory, including major settlements at the Quillayute and Hoh rivers; and at the mouth of Jackson Creek (Pettitt 1945). The Quillayute River, ranging only five-miles long, is the truck of a network of branching streams that are fed by continual glacial meltwaters from the Olympic Mountains.

The settlement of La Push arose due to its proximity with the mouth of the Quillayute River and the Pacific Ocean. During the summer months, families temporarily dispersed in smaller groups to access seasonal resources. While some moved inland to hereditary hunting, fishing, and/or gathering locations in the inland prairies, others kept to the coast seeking out marine resource locations (Powell and Morgenroth 1998).

Regardless of settlement location, the dietary staple of the Quileute has traditionally been fish, primarily salmon. Shellfish, smelt, herring, cod, and halibut are among other species consumed. They are “ranked among all tribes in the area as sealers” and traditionally hunted whales, sea lions, sea otters, and porpoises (Pettitt 1945). While all tribal members may have participated in fishing in a specific season, occupations such a whaler or sealers were exclusive, typically reserved to those whose guardian spirits were connected with a specific occupation.

The same type of division of occupation was extended to roles such as medicine men, canon- making, and even designated beggars (Pettitt 1945). The social, as well as logistical roles occupations, served, reflecting the environmental conditions of coastal life. The Quileute were adept at using tools in order to utilize their surroundings. Like all coastal tribes, canon, plank houses, weapons, and other items were manufactured out of felled trees. Cedar bark skirts and other clothes were also created. Animal skins such as rabbits and bears were used for protection against cold weather.

Traditional Quileute language is a part of the Salishan family and is related to Chimakum, part of the Chimakuan Family, once spoken near Port Townsend, but became extinct by the 1930s. Many anglicized-Quileute place names are found in the areas but have such as Calawah which translates to “in the middle” and Bogachiel (bókwaćhi’l) which means “muddy waters” (Powell and Jensen 1976).

Historic Period

One of the earliest recorded interactions between native peoples of the Olympic Peninsula and Europeans occurred in the 1770s with two separate Spanish expeditions. In 1774, Juan Perez sailed the frigate Santiago with a crew comprised of mostly Mexicans. Setting sail from Mexico, Perez surveyed the western coast of the future United States. He reached the Pacific Northwest during the summer of 1774 where he encountered the Haida, a first peoples group located in British Columbia, Canada. A second Spanish expedition commanded by Bruno de Hezeta also reached the northwest coast in 1775. Accompanied by the smaller schooner known as the Sonora, the expedition departed from Monterrey. On July 11th, Hezeta anchored several miles south of the mouth of the Quinault River at Point Grenville (Sanchez 2004). The expedition encountered the Quinault Indians at this location which met the Spanish crew of the coast by canoe.

This first interaction included the Spanish accompanying the Indians to shore, making them the first Europeans to set foot in Washington. After several rounds of friendly trading, Commander of the Sonora, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, sent a party of seven crewmen in a small landing boat to shore. The crew was quickly massacred by several hundred Quinault waiting in ambush. Following the attack, warriors pursued the Sonora, anchored offshore in deeper water. Bodega ordered boarding Indians shot, preventing the total annihilation of his crew. After the indecent, the Sonora rendezvoused with Commander Hezeta and the Santiago who was anchored nearly a mile away. The remaining crew voted to continue their voyage without seeking retribution (Sanchez 2004).

Following the course plotted by Hezeta and Bodega, the expedition established a settlement at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island in 1789. However, a discrepancy over Spanish claims to the area soon resulted in an attempt by Captain Esteban Jose Martinez to establish Spanish authority over what had become an international trading post (Guzman and Crowley 2006). As a result, the Spanish signed the Nootka Convention with the British on October 28th, 1790, relinquishing their exclusive claim on the area.

Following the incident at Nootka, present-day Vancouver Island, the Spanish established a settlement on the other side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The goal was to have a base to project political and military influence within the region. The Viceroy of New Spain sent Salvador Fidalgo to oversee the endeavor. In late May 1792, Fidalgo anchored near Cape Flattery and began clearing trees and building an encampment. The settlement was fortified with mountain guns, and a smithy, bakery, and corral for cattle were built (Banel 2019). Conflicts between the Spanish and nearby Makah Indians soon arose, and violent disputes resulted in deaths on both sides. Within four months of establishing a settlement, the Spanish withdrew from Neah Bay due to ongoing hostilities and the inclement weather of the area.

Euro-American settlement of the Puget Sound region grew steadily in mid-1800s. Timber harvesting operations established mill towns, often located near the coastline due to the difficulty of overland transportation. By the 1850s, large and small mills were operating near the east coast of the Olympic Peninsula in places like Port Gamble. Between 1855 and 1856, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens negotiated a series of treaties with tribes of the Olympia Peninsula. These included the Treaty of Neah Bay and the Quinault Treaty, which dispossessed the Olympic Peninsula tribes of the traditional lands and confined them to specified reservations. A reservation was created around the village of La Push in 1889 (Van Pelt 2007).

Although the land was officially opened to non-native settlement, few white settlers entered the area until the late 1800s. Settlement occurred earlier on the eastern end of the Peninsula with towns such as Port Angeles and Port Townsend being established in the early 1860s. Civilizational staples such as a port, lighthouse, and subdivided lots helped develop these early settlements into burgeoning towns by the 1880s. But American settlement of the Olympic Peninsula’s West End was slower to mature. Pioneers did not arrive in the areas around the Quillayute Prairie until the mid-1860s. Prior to overland entrance into the area, whites were known to the Quileute as ho kawt (“the drifting house people”) in reference to their ships (Powell and Jensen 1976). The terrain of the Peninsula made overland travel between the east and west side nearly impossible. For this reason, early settlers slowly made incursions into the area mainly by following rivers and trails from the Pacific Ocean and Strait of Juan de Fuca (Van Pelt 2007.)

Fur trappers we some of the first white men to settle the area. But by the late 1870s, families began to establish homesteads near the present-day City of Forks. The rich soil of the prairie supported hay, oats, grain, vegetables, and hops. Orchard trees were planted and dairy cows were introduced around 1880. In 1882, a school was established at La Push by A.W. Smith. When a post office was established in 1884, the name Forks Prairie was given due to the location between the Calawah and Bogachiel rivers. Still, the area remained largely isolated due to the impenetrable nature of the central peninsula. While the product could be developed, transporting it to market remained a significant problem. Foot trails were the most advanced form of overland travel until the late 1920s when surfaced roads appeared. (Van Pelt 2007).

The hard business of transporting goods to centers such as Port Angeles may have made trade with the nearby Quileute from La Push and Mora a necessity. When the trading post moved to Forks in the early 1890s, the settlement possessed a general store, hardware store, and hotel. Major logging activities in the area employed settlers from Forks in the early 1900s. Despite the designation of over 600,000 acres of forest as reserve land by 1907, logging continued to be a large industry in the area. When the United States entered World War 1, the Aircraft Production Board built the thirty-six-mile-long Spruce Production Division Railroad No. 1 on the Olympia Peninsula near Lake Crescent. In total, thirteen railroad lines were built between Port Angeles to Lake Pleasant (Tonsefeldt 2005).

REFERENCES

Ames, Kenneth M., and Herbert D. G. Maschner. Peoples of the Northwest Coast, Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson Ltd., London. 1999

Guzman, Gonzalo with Walt Crowley. “Mexican and Spanish settlers complete Neah Bay Settlement in May 1792.” Historylink Essay # 7953, September 20, 2006. Accessed January 2022. https://www.historylink.org/file/7953

Matson, R. G. and G. C. Coupland. The Prehistory of the Northwest Coast. Academic Press, San Diego, California, 1995.

Moss, Madonna. Northwest Coast: Archaeology as Deep History. Society of American Archaeology Press. Washington, D.C., 2011.

Nelson, C. M. Prehistory of the Puget Sound Region. In Northwest Coast, edited by Wayne P. Suttles pp. 481-484. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 7, W.C. Sturtevant, general editor, Smithsonian Institute, Washington D.C. 1990.

Pettitt, George A. “The Quileute of La Push: 1775-1945.”Anthropological Records, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960. Accessed November 2021, https://archive.org/details/quileuteoflapush0014pett/page/n3/mode/2up

Powell, Jay and Vickie Jensen. Quileute: An Introduction to the Indians of La Push. University of Washington Press, January 1976.

Powell, Jay, and Chris Morgenroth III. “Quileute Use of Trees & Plants: A Quileute Ethnobotany” Submitted to the Quileute Natural Resources, 1998.

Sanchez, Antonio. “Bruno de Hezeta (Heceta) party lands on Future Washsington Coast and Claims the Pacific Northwest for Spain on July 12, 1775.” Historylink Essay # 5690, April 22, 2004. Accessed January 2022. https://www.historylink.org/File/5690

Tonsfeldt, Ward 2005 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for U.S. Army Spruce

Van Pelt, Julie. “Forks—Thumbnail History.” Historylink Essay # 8397, December 10, 2007. Accessed January 2022. https://www.historylink.org/file/8397

Also See: History | Quileute Tribe (quileutenation.org)

Publish date