History of Quillayute Naval Auxiliary Air Station and Quillayute Airport

The beginnings of military aviation in the United States can be traced to the American Civil War with the utilization of air balloons for reconnaissance and supply transport. Heavier than air flight began in the late 1890s when Samuel Pierpont Langley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, designed a steam-powered tandem-winged machine called an “aerodrome” (Kindy 2021). Once Wilbur and Orville Wright successfully developed the airplane into a practical flying machine, military application of the new technology was not far behind.

The first military airplane was built in 1908 by the Wright brothers for the United States Army Signal Corps, the precursor to the Air Force. Although the United States was the first military to field a modern airplane, it failed to develop the infrastructure needed to support commercial and expanded military aviation. At the start of the First World War, many planes owned by the United States military were either obsolete or out of service. Moreover, the country lacked a sufficient number of aeronautical engineers, skilled workers, and airfields.

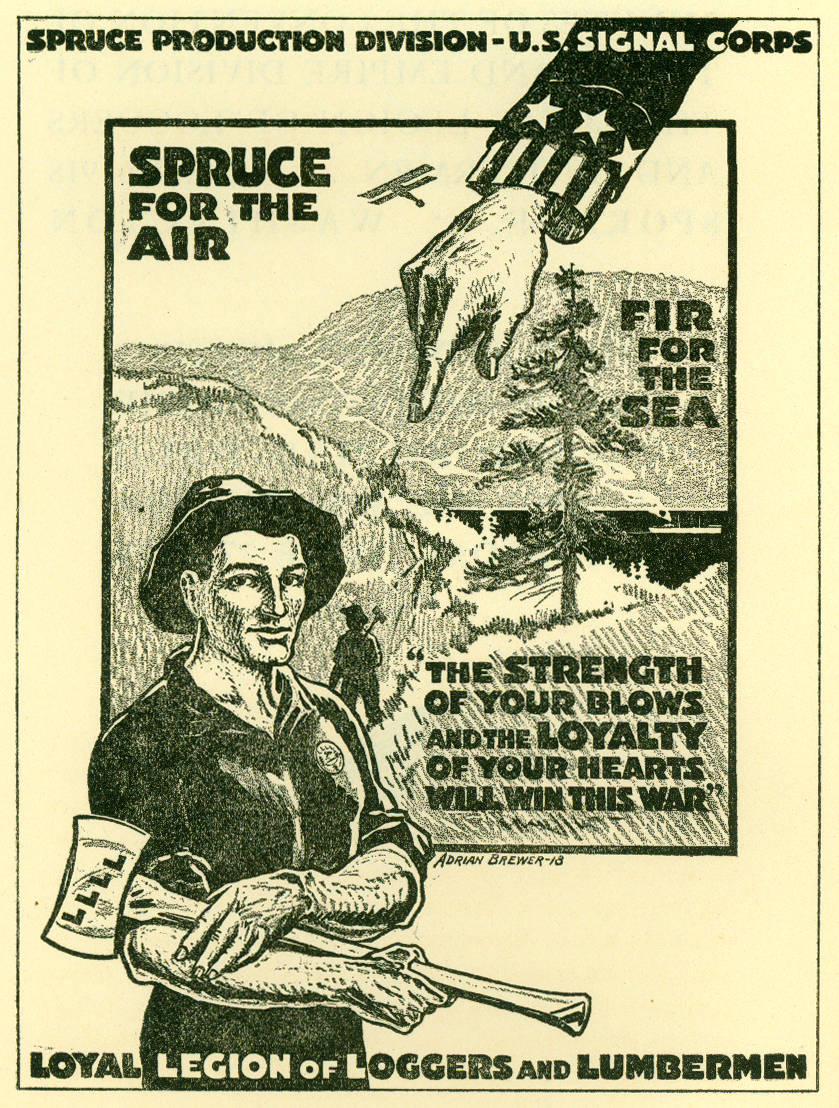

The Aircraft Production Board was formed in 1917 as a wartime response to build up the country’s aviation capacity. The Board prioritized the production of one airplane design, the De Havilland, whose design required spruce lumber for its frame. The Army Signal Corps organized spruce logging and milling operations in the Pacific Northwest, which was the principal source of spruce [Figure 1]. In 1917, the thirty-six-mile-long Spruce Production Division Railroad No. 1 was constructed on the Olympia Peninsula near Lake Crescent. In total, thirteen railroad lines were built in the northwest (Tonsefeldt 2005). Although the war ended before the railroad could be completed, it symbolizes the important role the area has played in the development of U.S. Military aviation.

Figure 1. Frontispiece in a booklet entitled "Minutes of the Convention of the Inland Empire Division of the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, June 22, 1918, Spokane, Washington" Source: University of Washington Digital Collections, Pacific Northwest Historical Documentation Collection

Support for aviation development floundered in the years following the armistice. The uncertainty of the post-war period saw the Army Air Service reduced in size as the country reestablished its reliance on seapower. Despite these trends, the Navy retained its interest in naval airpower, establishing the Bureau of Aeronautics in 1921. In addition to producing the first aircraft carrier, the Air Service established the components fundamental to military aviation and the establishment of the commercial air industry. Although airmail service had been established by the US Post Office in 1918, the development of an infrastructure of “aerial roads” by the Army Air Service helped it and other commercial aeronautical ventures establish a coherent system of the scheduled flight.

By 1925, airports began to appear along the first Transcontinental Air Route that had been developed by the Air Mail Service. Once the Post Office was authorized to contract air services to private contracts, the industry saw a boom in the establishment of new air routes. The 1926 Air Commerce Act was the first Federal legislation that regulated civil aeronautics. Safety standards, airway routes, and promotion of airports were soon developed by the Department of Commerce’s Aeronautics Branch. The legislation prohibited the Commerce Department from directly subsidizing airport construction, but relief funds were made available during the Great Depression for the development of airports.

Beginning in the 1930s, a number of Washington communities built or purchased existing airports, in large part to accommodate postal service flights. Using funds provided by the Depression-era Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Public Works Administration (PWA). The Forks Airport was not created using federal aid money. Rather, the airport was developed using private money beginning in the 1920s or 1930s (Fleck 2021). [Mansfield family, hops,] Initial construction of a single landing area measuring approximately 125-feet by 2570-feet. By the 1940s, a stabilized runway was constructed northeast of the existing strip.

Assessment and Selection of the Quillayute Prairie

The slow growth of the American aviation section was soon given a boost by world affairs of the late 1930s. Growing tensions in Europe and fears of an attack by the Japanese Empire on the West Coast led the United States Military to purchase or lease a number of municipal and private airports to be quickly converted to military fields. While the first military Air Station on the Olympic Peninsula had been built in 1935 by the Coast Guard at Ediz Spit in Port Angeles, it was recognized by Thirteenth Naval District that expanded forces were required to adequately defend against invasion (Pettitt 1945).

In 1940, a report was given to the Commandant of Naval Air Center, Seattle, detailing the Quillayute Prairie as a potential site for a Naval landing field. The area was one of several selected sites that were potentially hospitable to construction and within a “reasonable radius of the Naval Air Station and Naval Supply Depot, Seattle.” The report recommends the Quillayute Prairie as the ideal location for an auxiliary air station due to its position approximately 4-miles from the Pacific Ocean and roughly 60-miles south of Cape Flattery and the Juan de Fuca Strait. Naval reports indicate that no other viable alternative existed in the area due to the mountainous and wooded terrain of the western Olympic Peninsula.

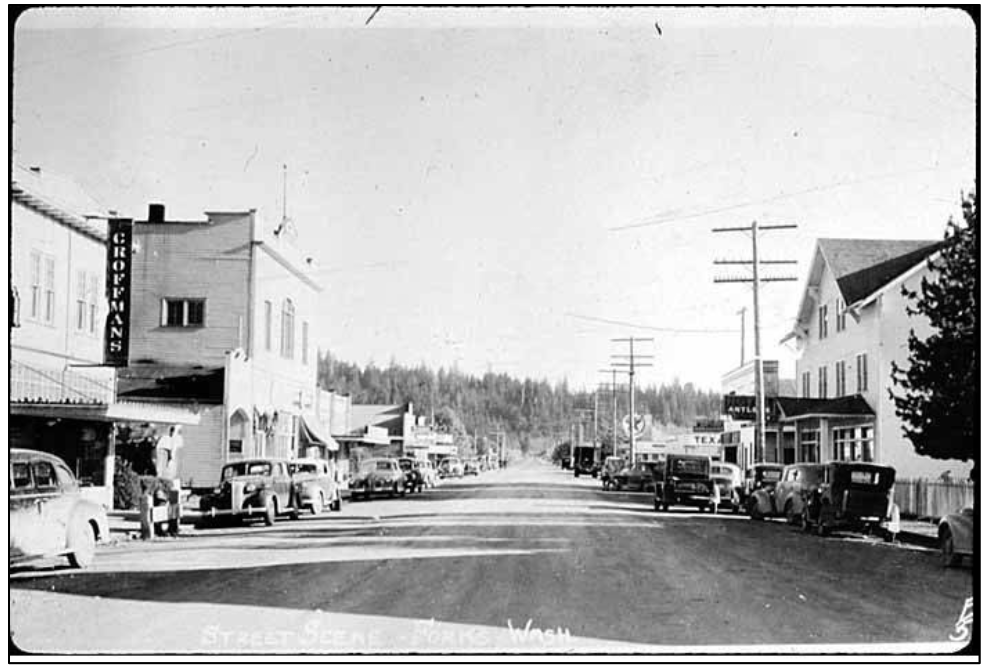

In addition, the nearby town of Forks was assessed in tandem with the potential recreation opportunities for Naval personnel. Early assessments of the town were not particularly positive with respect to troop entertainment. The report stated that “…The town is a normal, average town of 600 population, but it is felt that the enlisted personnel would not care much for liberty at this place.” But other opportunities for recreation such as hunting and fishing abound. Additionally, the report highlighted the “three beer parlors dispensing to sailors over 21, and dances are held at least once a week in the Odd Fellows Hall” (Tait 1942).

Photo 1. City of Forks 1935. Source, Forks Timber Museum.

Naval officials considered improving the existing municipal airfield at the town of Forks. However, the field was found to be too small and could not be adequately expanded. It was believed that an airfield at Quillayute might have a “tactical advantage in putting squadron aboard or taking them off carrier” (Dobbins 1944). Additionally, the area possessed a low population which presumably would aid in security.

Initial Development of Naval Auxiliary Air Station Quillayute (NAAS Quillayute)

In November of 1940, a recommendation was made by the Navy to the Bureau of Aeronautics for the purchase of 520-acres of land at the Quillayute Prairie at an estimated cost of $24,400. On the same day, notice to the Clallam County Board of Commissioners was issued by the Navy declining its plans to lease the emergency landing strip at Forks due to its inability to expand the field. The land was officially acquired by “taking” or eminent domain by the ruling of the U.S. District Court Northern Division of Washington. This ruling forcibly removed existing residents, all of which were family farms, from the area. Records do not detail a specific amount paid but appraisals of the land place it roughly between nineteen and eighteen thousand dollars (Pettitt 1945).

The initial plan was that Quillayute Naval Auxiliary Air Station (NAAS) was to be the second outlying field to be developed within proximity to Seattle. The Resident Officer in Charge of contract for construction was authorized to take possession of all unimproved land on April 10, 1941. Construction of the field began on May 2, 1941. Initial work was carried out by the Austin Company, with an allotted budget of $90,823.00. The first landing strip was completed on October 24 of that year. The graveled strip measured 300-feet wide by 4290-feet long. small hanger (20-ft. x 63-ft.) and a restroom that measured 20-ft. by 14-feet. No other buildings were erected. Farm buildings already present on the property were retrofitted to serve as barracks capable of house 25 officers and 50 enlisted men. Construction required the closure of 6000-feet of existing county road. Negotiations to relocate this road began soon after, By December 1942, Clallam County Board of Commissioners deeded the Navy 1,839 acres of land formerly used as County Road.

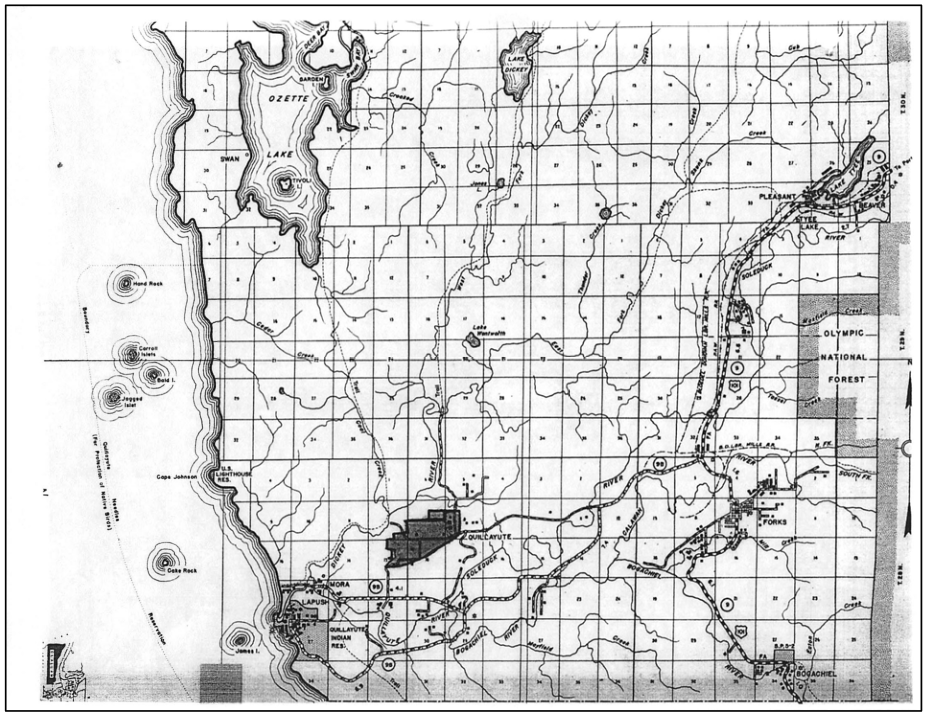

Joint Use and Development with Army Air Corp

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Army Air Force began opening airstrips with the stated purpose of stationing interceptors and pursuit squadrons. Within four days of December 7, 1941, the Army requested the use of the Quillayute Air Strip and other outlying fields. The Navy immediately authorized joint use of the facility and urged the Army to further develop the field. Naval approval for use by the U.S. Army’s Second Air Force was soon extended to the Fourth Army Air Force, who proposed considerable increases to the station’s landing strips. The Army also sought acquisition of an additional 525-acres of land adjacent to the Navy’s 520-acres (Figure 2). Soon, the Commander of Aircraft for the Northwest Sea Frontier requested that facilities for emergency landings of seaplane be constructed at Lake Ozette, approximately 7-miles north of the air state at Quillayute (Pettitt 1945).

In April 1942, approval was given for the Army to develop Navy fields. After the Fourth Army Air Force was granted priority to make improvements to the airfield at Quillayute, a produced a figure of $856,000 for expansion of its runway and other necessary improvements. This figure was far greater than the expenditures already made by the Navy at Quillayute.

Records report that “little action was taken with regard to establishing of an Auxiliary Air Station on the foundation laid in 1941 [by the Navy] until December 1942.” While the existing airstrip and land were owned by the Navy, it was unclear if the Army would be justified in condemning the field as it was the branch proposing the improvements. It was eventually confirmed that the Navy would reimburse the Army for its expenditures on all Navy-owned fields (Pettitt 1945). However, communication between the Army and Navy regarding improvements appears to have been unclear, if not fraught with jurisdictional concerns.

Figure 2. U.S. Army Air Corps maps of Quillayute NAAS, 1942.

Photo 2. Aerial photograph of Airfield Quillayute, 1942. Source, U.S. Army Air Corps.

However, due to the inefficient communication between the two service branches, delays and other logistical issues continued until 1943 when the Army officially withdrew. For example, the Army pressed forward with its plans to develop the facility without consulting the Navy regarding changes to the final plans. Upon authorization of the funds by the Navy, engineers concluded that the new airstrips would be constructed using concrete instead of the more common asphalt due to ready access of the material. This change in design increased the final estimate to $1,166,540. Navy engineers estimated this cost closer to $1,514,970. During construction, the Navy did little to assist in Army’s efforts, asides from clearing legal hurdles to relocate a Clallam County Road. The Army sought acquisition of an additional 525-acres of land to the Navy’s 520-acres. However, questions soon arose regarding which branch would provide funds for improvements to the air station. Issues surrounding joint usage of the Station plagued the development of the facility through 1942 (Pettitt 1945).

In the fall of 1942, Lieutenant Commander Robert N. Dobbins volunteered to serve as the commanding officer of the new air station. Dobbins brought nearly twenty years of experience in the young field of aviation, primarily gained in the private sector. Dobbins was an experienced aviation machinist and mechanic having worked for companies such as Curtiss-Wright and Canadian Colonial Airlines in that capacity (Pettitt 1945). He was a certified pilot and worked as an aerial photographer, charter pilot, and instructor. He earned his Batchelor’s of Science in Mechanical Engineering from Newark College in New Jersey in 1939. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed supervisor of War Production Training for the New Jersey area. In September 1942, Dobbin’s was granted a reserve commission by the U.S. Navy. After attending a flight refresher course in Pensacola, Florida, he was ordered to Naval Air Center, Seattle.

Photo 3. Robert N Dobbins, Lieutenant Commander of NAAS Quillayute.

During negotiations between the Navy and Army over development of the Station, Quillayute served as an emergency field solely for Navy use. In November 1942, it was designated as a training center for “one-half a CV group (45 land planes or 12 VB planes, and 2 SNP; Emergency).” By December, it was selected as the future base for 90 carrier vessel (1 CV group) planes, 24 vessel bombers (VB) planes, and two (2) ZNP Emergency; better known as a dirigible, airship, or blimp. These changes would make the air station the largest within the Seattle area. The first contract for construction was let the Army Engineers and called for the clearing and construction of housing. The contract was awarded to Sullivan, Lynch, and Hainsworth for a total cost of approximately $72,000. Working conditions were difficult due to the extreme rainfall of the Quillayute area. Washington newspaper periodically reported on the military’s multiple expenditures during the establishment of the Quillayute NAAS.

Construction on the base and newly acquired acreage began in early 1943, using plans designed in 1942. The base was to provide for Navy training and Army defense activities such as protection against aerial attacks. Plans called for housing units located a mile and a half from the hanger. Gasoline storage tanks were to be scattered around the facility’s perimeter which was to have approximately “two miles of concrete taxiways and hardstands forming an elaborate dispersal area for planes.” The Army did not follow the original grading of the Navy-built runway, instead, shifting direction slightly. Twenty-one buildings were built at the northeast corner of the station and including barracks, mess hall, dispensary, heads (restrooms), and officers’ quarters.

Despite the persistent urging of the Navy, official authorization for new construction was not given by Washington as of March 1943. Instead, approvals were given by Washington to develop an air station at Mt. Vernon. On April 15, 1943, the Commander of Fleet Air, Seattle wrote directly to the Commander at Naval Air Center, Seattle stating that the development of the Quillayute station was “emphatically important” based on its location and ability to house ample gunnery stations. The letter further emphasized that the development of the air station at Quillayute would in effect, render the Mr. Vernon base irrelevant.

That May, after endorsement by several naval officials, including the Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, the Vice Chief of Naval Operations gave the approval to cancel construction at Auxiliary Air Station, Mt. Vernon in favor of construction at Quillayute. However, approval to proceed with the development of Quillayute was limited to the exact funding amount of $965,000, which was previously authorized for Mr. Vernon.

This amount was well under the estimated cost of construct made by both Army and Navy engineers. On May 4, 1943, the Officer in Charge of Quillayute issued a report that indicated that at least $1,288,000 was required to complete developments planned by the Army. The report and subsequent correspondence further requested new laundry facilities; infrastructure such as power, heating, sewer, water, and phones; a new Hanger, control tower, cold storage; and construction of a second runway to facilitate long-range patrol bombers. The Spokesman-Review of Spokane reported that in May, $71,000 was required to construct a “celestial navigation trainer building”. By the end of the month, a new estimated amount between $2,014,000 and $1,049,000 to complete construction at Quillayute.

By late August, personnel began arriving in Seattle, awaiting assignment to Quillayute. By October, approximately 100 men were awaiting living quarters to be constructed at the Air Station. Housing for enlisted men and officers with families was both limited on the station and in the nearby town of Forks. Dilapidated lodgings and other non-residential structures were repaired and converted to house military personnel and civilians. Trailer camps and housing units were built at Forks specifically for “war workers” by the Federal Housing Agency (FHA). Some trailer houses owned by the FHA were eventually converted to use by Navy personnel.

In February 1943, the Navy held a joint conference with Army officials in Seattle. The purpose of the meeting was to inform the Army of the Navy’s intentions to further develop its outlying airfields in Washington. It was noted that the Army was not excluded from using these properties, but it was emphasized that the Army was, in fact, not utilizing these facilities.

Return to Navy Occupation and Development

In October 1943, the Army unofficially ended its efforts to improve Navy-owned fields in the State of Washington. The reason given in a letter addressed to the Pacific Division of the U.S. Engineers seemed to return to the initial discrepancy over Navy ownership of the field and joint use by the Army. However, the official reason was attributed to “change in the war situation” (Pettitt 1945). In November, it was recommended by the Fourth Air Force Operations that all Army facilities be transferred to the Navy. Despite this development, it was not until September 1944 that the Army officially detached from NAAS Quillayute.

Between October to April, the rainfall average was 100-inches or more. The rough terrain of the area and rural location created obstacles in the transportation of materials. With few improved roads and nearly nine miles from the nearest railroad connection, all materials had to be trucked in, typically from Port Angeles, Bremerton, or Seattle. Water wells, electrical power, and housing for civilian contractors and military personnel were also constructed. However, due to the lack of eligible laborers in the area, workmen had to be relocated from other places. Conditions caused by the continuous rain and isolated environment caused heavy staffing turnover, delays, and higher costs.

Photo 4. Apron adjacent to existing hanger, date unknown.

Construction slowed during the month of December. The lack of qualified mechanics resulted in the limited progression of the station’s power plant and electrical system. Footings and foundations for the dispensary were poured, and the ground was prepared for the laundry and cold storage buildings (Dobbins 1945). A monthly report addressed to the Commandant at N.A.C., Seattle, reported the status and activities at NAAS Quillayute. The information provided detailed that the majority of personnel stationed to the base were assigned for security as the station was still under construction and “still on a pre-commissioning basis”. Some were placed on special assignments with activities located near Seattle. Several commandants from N.A.C., Seattle inspected the Station multiple times during the month of December.

As negotiations between the Navy and Army for decoupling were underway through early 1944, Navy activity at NAAS Quillayute continued. In December 1943, there were thirty-three men under the charge of four officers on station. Although all of the Army’s properties had yet to be officially transferred to Navy control, construction continued on Station in 1944. On Christmas Day, the employees of the Public Work Department arrived to build permanent buildings.

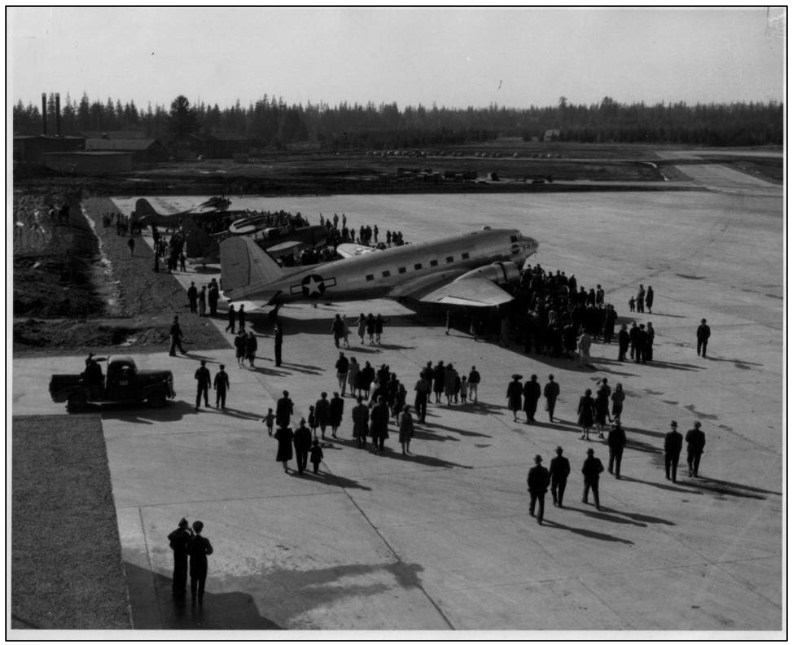

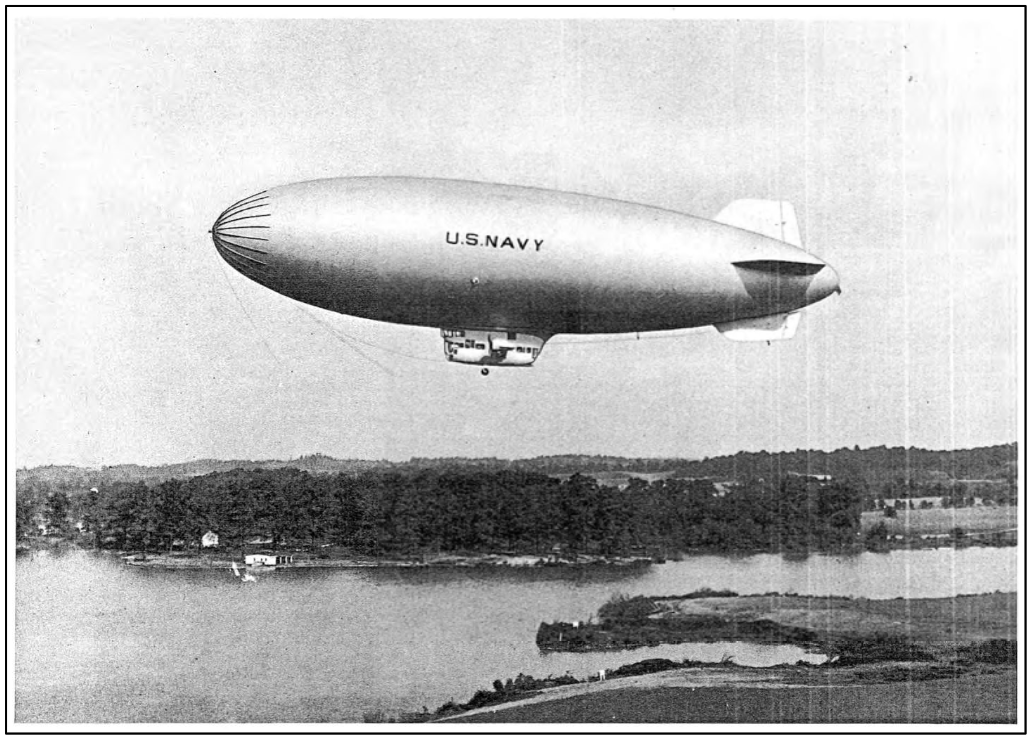

By January 1944, the Army Air Force withdrew its guard detachments from all Navy bases in the northwest. Nearly 133 Navy personnel were assigned to NAAS Quillayute, with 47 located on Station. The next month, John J. Bergen, the Commander of U.S. Naval Reserves, visited the Station as the Acting Commandant, representing the Naval Air Center (N.A.C), Seattle. Commander E. J. Sullivan of Squadron 33 accompanied Bergen and represented Naval Air Station (NAS), Tillamook. He and five officers made the trek in a K-33 Airship. These officers, along with others, were in attendance for “commissioning day,” both the official opening of NAAS Quillayute as well as the assignment of duties to the Station’s officers. Conservative estimates placed the attending crowd around seven hundred people, many civilians from the nearby town of Forks.

Construction slowed during the month of December. The lack of qualified mechanics resulted in the limited progression of the station’s power plant and electrical system. Footings and foundations for the dispensary were poured, and the ground was prepared for the laundry and cold storage buildings (Dobbins 1945). A monthly report addressed to the Commandant at N.A.C., Seattle, reported the status and activities at NAAS Quillayute. The information provided detailed that the majority of personnel stationed to the base were assigned for security as the station was still under construction and “still on a pre-commissioning basis”. Some were placed on special assignments with activities located near Seattle. Several commandants from N.A.C., Seattle inspected the Station multiple times during the month of December.

As negotiations between the Navy and Army for decoupling were underway through early 1944, Navy activity at NAAS Quillayute continued. In December 1943, there were thirty-three men under the charge of four officers on station. Although all of the Army’s properties had yet to be officially transferred to Navy control, construction continued on Station in 1944. On Christmas Day, the employees of the Public Work Department arrived to build permanent buildings.

By January 1944, the Army Air Force withdrew its guard detachments from all Navy bases in the northwest. Nearly 133 Navy personnel were assigned to NAAS Quillayute, with 47 located on Station. The next month, John J. Bergen, the Commander of U.S. Naval Reserves, visited the Station as the Acting Commandant, representing the Naval Air Center (N.A.C), Seattle. Commander E. J. Sullivan of Squadron 33 accompanied Bergen and represented Naval Air Station (NAS), Tillamook. He and five officers made the trek in a K-33 Airship. These officers, along with others, were in attendance for “commissioning day,” both the official opening of NAAS Quillayute as well as the assignment of duties to the Station’s officers. Conservative estimates placed the attending crowd around seven hundred people, many civilians from the nearby town of Forks.

Photo 5. Commissioning Day ceremonies, February 29th, 1944. Sources, Forks Timber Museum Digital Collection.

The War Manpower Survey Board visited the Station on February 22 nd , 1944 to assess the Station’s readiness. The survey found the Station to be in good condition with a satisfactory utilization of staffing. After a long delay, mechanics were dispatched by the Radio Materials Officer’s office in February 1944 to finally install the necessary radio equipment at the Station. Around that time, telephone systems were installed as well as weather and administrative teletype circuits. As construction continued, clearing operations were required to make way for the new construction. But the work was not without its potential hazards. On March 22 nd , two employees of the Dunlop Towing Company reported that two of its employees drowned in the Dickey River, presumably during tree clearing operations.

Despite slow progress and the occasional accident, primary construction was completed in April 1944. However, many small items remained unfinished and would plague the Station over the course of the year. While many of the buildings were completed, installation of equipment and continued electrification efforts were required to finalize construction. This work in the dispensary building was finished on April 30th.

Although the Army no longer had a physical presence at Quillayute, the official transfer of Army property at Quillayute to the Navy occurred on September 18, 1944. The seven-month gap between announcing its withdrawal and officially relinquishing control of Army properties at Quillayute was reportedly due to finalizing reimbursement of its expenses with the Navy. The final agreement stipulated that neither the Army nor the Navy would reimburse costs for facilities utilized by only one branch of service on fields owned by the other service. Presumably, this meant that the Navy did not reimburse the Army for facilities it built at the NAAS Quillayute for sole Army usage (Pettitt 1945).

Pressures to complete the station persisted throughout the first weeks of 1944. Delays caused by inclement weather, labor turnover, and funding approvals, began to mount. The minimum facilities and unfinished nature of the station prevented the assignment of a squadron and hampered the commissioning of any officers. More equipment, such as tractors and trucks, were requested to complete the work. In addition to construction, the organization of various services and infrastructure requirements were needed. Barracks, recreational facilities, and a library all required attention. Moreover, the station required 50 tons of coal, per week, be shoveled and transported by truck from the nearest railroad.

Construction on personnel housing and other related building continued into the summer of 1944. Two Bachelor Officer Quarter’s (B.O.Q.) were completed around April. Laundry facilities soon followed. Additional construction was hindered by restraints imposed on NAAS Quillayute by monies obtains by the abandoned station at Mt. Vernon. By the time these issues were resolved, the primary contractor, The Austin Company, had finished its work and vacated the station. By late spring housing, mess facilities, and a host of other operations-related buildings were in place. However, many were still operating with non-permanent arrangements. For example, the completed control tower did not have radio equipment and relied on the use of a “short wave portable” set housed inside the station’s ambulance. The vehicle was parked next to the Hanger in order to reach planes on landing and take-off.

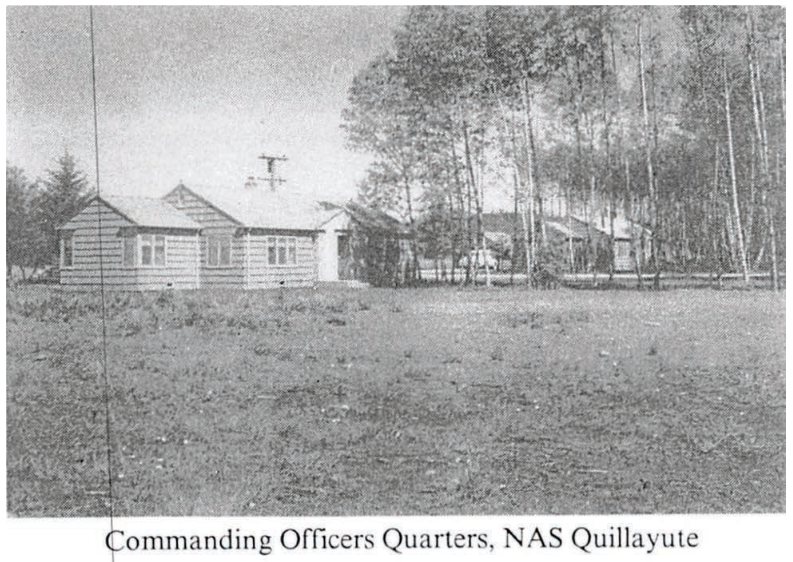

Photo 6. Commanding Officers Quarters located on Station. Source, R. N. Dobbins, “A Lifetime of Memories,” 1993.

In March, the station’s Fire Department experienced its first fire emergency when a contractor accidentally set blaze to nearly 10-acres of grass and wooden land. Operating from its temporary location inside the Hanger, the fire barraged effectively stopped the first before it reached the nearby Quillayute Elementary School. A permanent firehouse was completed in August by Vickers Construction Company.

By June of 1944, requests for housing off base increased due to limited housing available at NAAS Quillayute, particularly for married men with families. Additionally, conditions were not suitable for couples as showers, toilets, and laundry was located far away from living quarters. This was not adequate during the winter months on the pacific coast due to the enormous rainfall. In response, 20 additional housing units were approved for construction in September 1944. The following request secured another 34-housing units with laundry and storage along with an additional relief in the form of Quonset huts.

Soon after, four of the eight 80-man barracks were complete with four requiring some plumbing and finish work. Other infrastructure such as water and sewage systems were near 75-percent completed. Electrical distribution was approximately 95-percent completed but suffered from habitual failure of its two diesel-electric generators. The station ran on these two generators, built in 1914 and obtained from Casper, Wyoming, due to the inability to source adequate power from nearby Forks Light and Power Plant.

The station’s main water supply failed in June 1944 due to the breakage of its main turbine pump. Luckily, the turbine was repaired quickly with assistance from Naval Air Station Whidbey and N.A.C Seattle. However, a second failure of the water main occurred in late June when a pump’s motor burned out. The problem was attributed to the Station’s on-going problems with its power generator.

Around July 1944, the Public Works Department was assigned to build “essential structures” on the station. These included a garage for the Transportation Department, public works shop, recreation buildings, tennis courts, and dormitories for civilian employees. Work involved razing “shacks” left by the Austin Co. in addition to constructing these new structures. However, before this work could be completed, new construction plans were authorized that expanded the scope of buildings to be constructed. Plans authorized in June 1944, called for a “Free Gunnery Training Bldg. and a Class C Overhaul Bldg.” Housing for the Commanding Officer and the Senior Medical Officer were included.

Photo 7. Aerial of hanger and adjoined tower, 1945.

After some debate regarding personnel size and the number of complementing officers, it was decided in August 1944 that the station’s personnel would increase from “18 officers and 136 men to 27 officers and 199 men.” This figure did not include other outfits stationed at Quillayute which brought the “Ship’s Company” or total personnel on the station to 67 officers and 453 men.

Development of the Station continued through the end of the war. Interior work on the Married Officers’ Quarters was nearly completed in February 1945. An adequate supply of laborers, still an ever-present problem, continued to delay progress on construction efforts. Plans for a gunnery training school had been initially considered in the selection of Quillayute. These plans were to be implemented but were not expected to be in operation until March 1945. Delays pushed the project’s start date into February and were finally completed May 7th, 1945. The shooting end of the gunnery ranges were completed in July. By August, the gunnery range was 85-percent complete (Dobbins 1945). Other projects included the construction of the Radar Beacon Shelter and Rocket Range which were both mostly finished in late July.

Energy and Power

The station continued to operate without a reliable power supply as the power plants obtained from Wyoming were plagued with mechanical problems. The station operated with constant electrical issues through Commissioning Day, the official opening of the station. In February 1944, two connecting-rod bearings on one generator burned out. The second soon suffered a bent crankshaft, broken crankcase, and a house of other serious issues (Dobbins 1945). As of March 1, the decision had been reached to replace the antiquate and unreliable generators with six generators in Army and Navy surplus stock. In the interim, “a battery of Buda 37 KW generators” would be used to supplement the existing generators. In the meantime, issues continued with both the station’s diesel generators. Continued repairs and periodic outages of each unit were common. The situation became so dire that one generator or power plant was cannibalized for parts to keep the other unit operational. Even then “the plant broke down at irregular and usually embarrassing intervals.”

This reconstructed second generator was again off-line in early April due to broken parks such as burned-out bearings. Attempts to repair the power plant continued throughout the month but only resulted in new problems. Components were machined to replace broken parts but these repairs did not produce satisfactory results. The lack of this power plant resulted in serious deficiencies in the operation of the station’s electrical and radio equipment.

In May 1944, the power operated at 60-percent. This was down to 25-percent by July. Luckily a new Worthington Diesel-Generator arrived at the base in late July 1944. However, the unit was not operational until September. The new unit, now taking the lead, ran alongside the remaining 1914-vintage generator for only a few days. Finally, the troublesome generator was ordered to be shut down. The engineman on duty is reported to have said “now you can go to hell” as he switched the antique off. In November 1944, new gasoline storage buildings were completed with an additional six (6) standby generators installed in late December.

Transportation

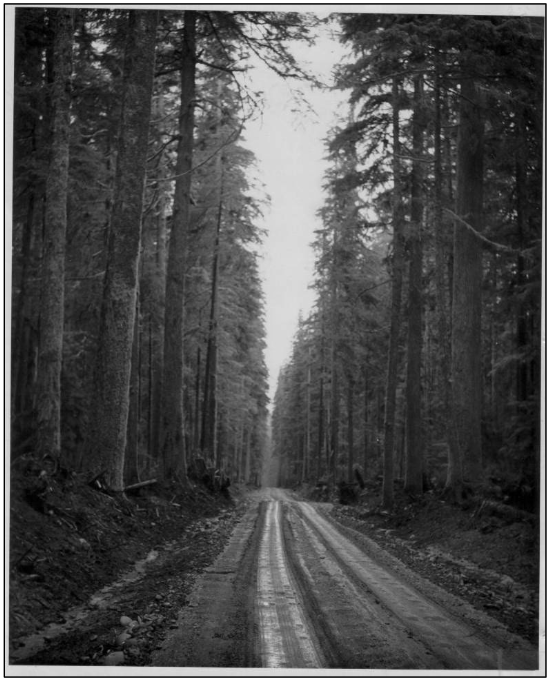

Overland travel was still an issue with regard to safety. Access to the base via primitive roadways caused “an epidemic of automobile wrecks” during the first few months of operation. These accidents involved personnel who were unaccustomed to unimproved roads. A report issued by Station Commander Dobbins, dated December 1943, described the condition of roads on the station as needing grading with much more work to be done (Dobbins 1945). A report written in February 1944 stated that the contractor had made “exceptionally good progress” on the roadways but delays persisted due to slow delivery of equipment. Plans for a new transportation building resulted in construction efforts which continued through June 1944.

Four vehicle accidents that occurred between June and July resulted in the deaths of two enlisted men and major damage to the vehicles involved. During the same period, six vehicles sustained either minor or major damage while traveling on station business while on route to Forks. The primary cause of the wreck was partially the graveled road surface and its extremely narrow prism. However, accidents were not the only problem created by the poor state of transportation at Quillayute. Many disciplinary cases were categorized as absent over leave (AOL) due to inadequate transportation from outlying areas.

Photo 8. “Quillayute Road”. Source, Forks Forum, Quillayute NAAS, December 30, 2020.

A petition to the Washington State Highway Department and Clallam County Board of Commissioners spurred the improvement of a primitive nine-mile-long road that connected NAAS Quillayute with US Highway 101. The Bureau of Yards and Docks (BuDocks), the Navy’s engineering and construction branch approved $20,198.00 for surfacing roads on the station. Surveying parties soon began work and continued to layout the next access road.

Due to the heavy need for vehicular transportation at other stations, few motor vehicles could be obtained for the station. This severely restricted the public transportation between the station and Forks. For example, NAAS Quillayute possessed a single bus that sat 32 men on Commissioning Day. Four to five trips to Forks, taking about 50 minutes each way, were required every Friday and Saturday night to facilitate some 150 seamen who visited local taverns. After several requested for additional busses, the Domestic Transportation Officer assigned a second bus to the station.

The Sound Construction Company began work on surfacing roads on Station in late July and completed their efforts on August 10, 1945. Entertainment, Education, and Faith at NAAS Quillayute. The sizable number of personnel raveled that of the nearby town of Forks. With its population of roughly 600, few activities were available to seamen during leave. Although Forks boasted some entertainment options, the fact that it was the only source of civilization within “some 50-miles in all directions” lead the station’s leadership to build its options for entertainment. Thousands of books stocked the station’s library as well as over 100 training films to aid in officer training and rating advancement. A wide array of recreational equipment was supplied by the 13th District’s Welfare and Recreation Office (WRO).

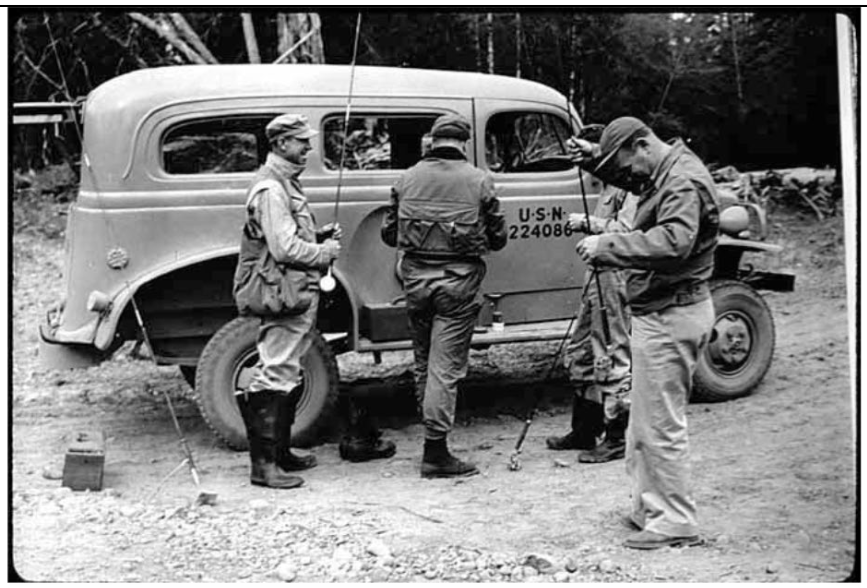

Hunting was plentiful given the wilderness surroundings of the Station. Deer and bear were regularly encountered on that installation and its runways. Citizens of Forks provided hunting licenses for enlisted men to be passed amongst seamen engaging in recreational hunting. In addition, Officer’s Mess was occasionally augmented by area game including salmon, trout, crab, bear, elk, venison, and various bird meat. Halloween 1944 was a feast of 62 geese that were provided by 30-officers. Some officers ranged picnics and swimming parties for enlisted men. A 35 MM motion picture projector was obtained from North Bend. On July 4th, 1944, WRO and the American Legion Sports competition between Quillayute and other area stations was a source of entertainment and pride. NAAS Quillayute won the Olympic Peninsula Invitational Basketball Tournament. Its football team had the second-most wins in the Olympic Peninsula League and won the district championship in December 1944. Its Pistol Team defeated the Port Angles Pistol Team at a competition in August 1944.

Photo 9. Seamen preparing to fish. Sources, Forks Timbers Museum.

The Quillayute Quill was the NAAS’ newsletter. The publication was intended as another source of recreation in an otherwise isolated environment. The paper was limited to a six-page announcement sheet that informed seamen of upcoming events. Additional special training for sentries, shore patrol, and fire department personnel was developed. Courses on fighting forest fires were particularly pertinent given the station’s location. Reading courses designed to increase competency were given to seamen determined to require additional education for advancement. While in-person trainings were given via the Education Officer and applicable staff, many programs were delayed due to inadequate film projecting equipment. The Station’s single 16MM project was unable to handle the constant demand of pilots, flight crews, and ground crews in addition to non-operation related trainings. Luckily, two projectors arrived In August 1944 for use by the planned gunnery school, that had yet to be established at NAAS Quillayute.

The United Service Organization (U.S.O.) hosted various events and forms of entertainment. It first assisted in Quillayute’s Commissioning Day ceremony. The U.S.O. hosted movies such as “Five Graves to Cairo”. Regular boxing and wrestling matches began in April. The first stage shows were put on, replete with an orchestra comprised of enlisted men and some sixty girls from the area. Although not included in the original plans, a baseball diamond and practice football field were cleared, graded, and seeded. By September 1944, two concrete tennis courts had been constructed. In December 1944, a recreation hall under construction by Public works and volunteer labor was nearly complete.

A chapel was not provided as the Station was not large enough. But chaplains were made available through N.A.C. Seattle’s “circuit-riding program” provided services to protestant and catholic personnel. Regular chapel services were organized in Forks in a variety of venues. Despite these attempts to provide spiritual support by the Navy’s traveling chaplains, the limited resources of local faith leaders were required to supplement the demand for religious services.

In May 1945, NAAS Quillayute participated in the V-E Day program in Forks. A firing squad and color guard was also involved in Memorial Day Services hosted by the Fork’s American Legion.

Aircraft, Training, and Rescue Activities

Early reports highlight the use of the Station as helpful in aiding distressed planes. Canadian and American planes utilized the facility’s runway in emergency landings. Engine troubles and fuel shortages were common issues that forced landings. Blimps or lighter-than-air craft (LTA) for Naval Air Station, Tillamook, Oregon used the base for touch-and-go landings on numerous occasions. In December 1943 a Douglas-R4D transport plane landed at the station. This was the largest aircraft to have visited the NAAS Quillayute at the time (Dobbins 1945).

Although incomplete, the Station proved to be a valuable resource for Navy aircraft and personnel who utilized its unfinished facilities for emergency repairs. In early 1944, two instances of Navy pilots of the Inshore Patrol used NAAS Quillayute due to mechanical issues. The close proximity of the Station was credited with saving Navy planes and lives. A PBY-5A Catalina seaplane and several other planes were forced to land at the station during the month of February due to bad weather.

In late February, two planes, a J4-F Widgeon and an SB2-A Buccaneer, were assigned to the Station. Two more planes, a Howard GH-2 and GB-2 Traveller were added to the Station’s fleet in May. These planes were used in routine flights but experience periodic mechanical problems which put them out of commission for any period of time. Repairs could be delayed due to a shortage or delay in parts. Other planes were assigned to the Station over the course of the war, some being the SNJ-4 Texan “bluebird” and GH-3 Nightengale (Dobbins 1945).

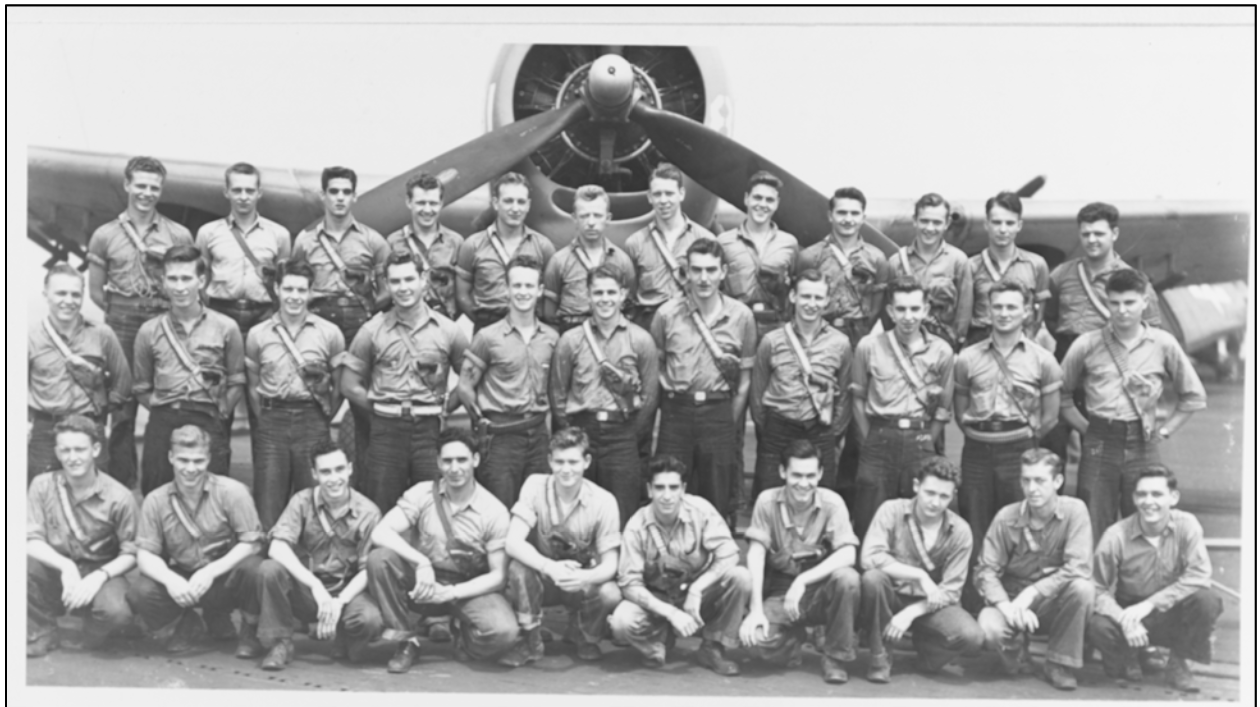

On March 22, 1944, “Composite Squadron VC-96” was assigned to Quillayute by Fleet Air in Seattle. Their stated purpose for being assigned to NAAS Quillayute was for training pilots in carrier operations (Denfeld 1996). Planes arrived on March 23rd and the one-hundred thirty-six (136) enlisted men arrived by bus on March 21st. The first flight of this group consisted of “15 FM1 (Wildcat’s) and TEM1’s” led by Lieutenant W.S. Woolen which occurred on March 25th.

During its six-month tenure, the squadron logged over eleven thousand flight hours while stationed at Quillayute. The training included booming and strafing practice. For this, uninhabited off-shore islands were used in these exercises.

Photo 10. Air crewmen of Composite squadron ninety-six (VC-96), photographed aboard USS RUDYERD BAY (CVE-81) on 24 April 1945. Source, Naval History and Heritage Command.

Around that time, a B25 bomber was forced to land on the beach near Kalaloch, Washington. The Coast Guard responded to this incident and informed NAAS Quillayute which initiated salvage operations. The determined cause for the emergency landing was a lack of fuel due to the plane departure from Anchorage, Alaska. While the entire aircraft could not be rescued from the encroaching tides, important components such as navigational instruments and radio gear were removed before the plane was hauled inland. The incident was reported to McChord field, who sent an Army salvage crew within twenty-six hours.

An ocean crash rescue group was organized around March 1944 in conjunction with the Coast Guard, who occupied the Quillayute Lifeboat Station at the nearby LaPush Indian Reservation. It was agreed that the Coast Guard possess the equipment and experience to lead the effort, the Navy agreed to provide a crash boat, a Pickett-38’ Navy #C018356, for use by the Guard (pg.15). The crash boat arrived via the Coast Guard Air Station, Port Angeles on April 11, 1944 along with a seaplane, the PBY-5A, and Coast Guard Air Sea Rescue Group to operate it. However, the equipment and crew were transferred to the Whidbey Island airbase where “it was felt there was a greater need for it.”

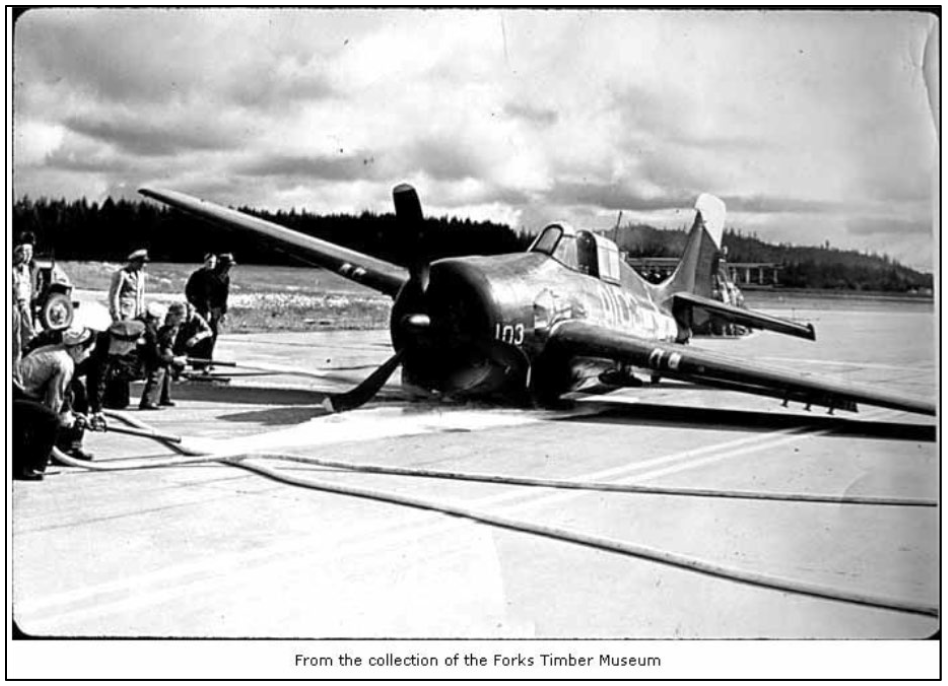

Within a month of its assignment to NAAS Quillayute, Squadron 96 suffered the loss of two planes and one pilot. The two crashes resulted in a request to relocate the PBY-5A Rescue Unit to Quillayute or the base at Lake Ozette. The first occurred on April 22nd when Ensign Robert McGowan crash-landed an FM-1 Wildcat at sea. He and the plane were lost. Within the month, a TBM Avenger crash-landed approx. 60-miles offshore. The crew was able to escape before the plane sank. A Russian freighter rescued the TMB’s crew as the sea-rescue unit at NAAS Quillayute had been ordered off station the day before. The Coast Guard Station at Port Angeles was the nearest air facility to the accident (Dobbins 1945). Negotiations between the Thirteenth Naval District and Clallam County Commissioners eventually resulted in an agreement to dredge portions of the Quillayute River channel in order to facilitate air-sea rescue operations. Dredging began on September 26th and was overseen by engineers from the Army.

Photo 11. An Airplane that crash-landed at Quillayute Naval Auxiliary Air Station, Circa 1945.

Continuing issues with rocks on the runway caused flat tires upon landing and present a general risk to aviation safety. A request for a motorized runway sweeper was approved with one such vehicle assigned to the station in April. Additional measures to improve runway safety included clearing of stumps and trees within 500-feet of each side. Seamen on loan from Fleet Air in the 13th District, Seattle were put to work “felling trees which projected above the surrounding forest to a dangerous height.”

The environmental and climatic conditions of the Quillayute oscillated between extremes. In the winter months, heavy rains and high winds restricted use of LTA craft and created challenging conditions for airplanes. Moreover, the abundant wildlife, namely migratory waterfowl, became a serious hazard to airmen taking off from the runway.

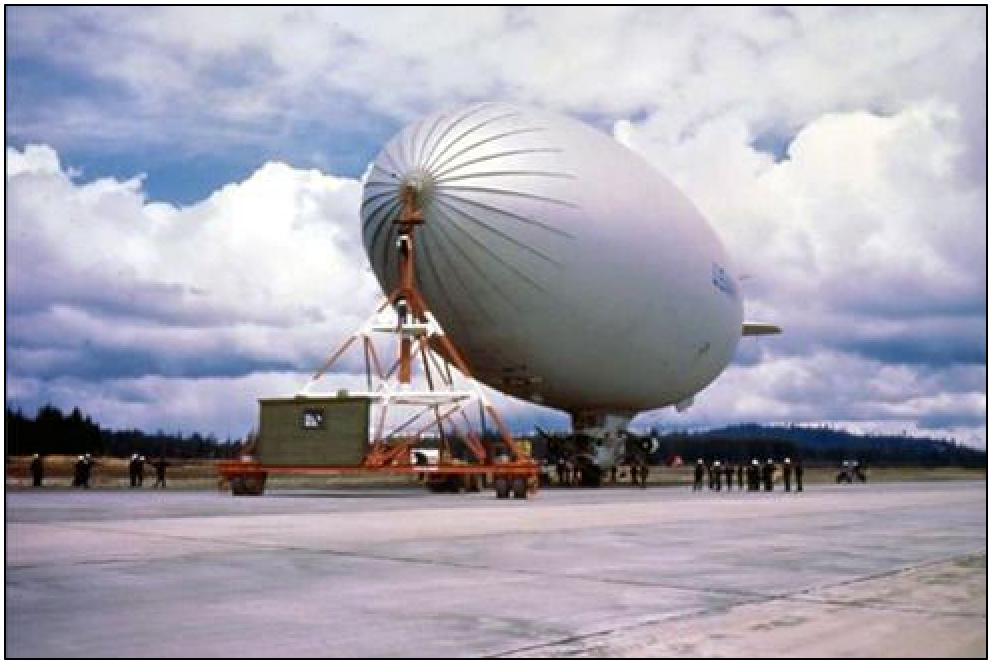

Photo 12. Blimp cockpit and crew on Quillayute runway, circa 1945.

The trouble caused by the two antique generators prevented night flights from occurring. Now, with its new generator, electrical field lighting was installed by the City Electric and Fixture Co in May 1944. Completion of the field lights occurred in September 1944, around the same time as completion on the new power plant. The lighting system was put into service in September, just after Squadron VC-96 left the base.

After the departure of its first squadron, a flurry of repairs and improvements were made to NAAS Quillayute. This activity was due in no small part to the uncertain arrival of the next squadron. The experience of its first flight crews lead the station’s leadership to remove some 250 trees that obstructed the line-of-sight of pilots and tower personnel. Gravelling of roadways, digging drainage ditches, construction of a second tennis court, and “scours of minor jobs” took place over the course of two weeks, likely between August and September 1944. During this period, an SNV Valiant that had been assigned to the Station was returned to NAS, Astoria for other assignments. The next squadron assigned to Quillayute was VC-72, who arrived on September 30th 1944. Good weather allowed for steady flight training over the course of the fall and early winter. One pilot, Ensign Grover C. Consford, died during a training exercise on October 19th, 1944. The accident, a mid-air collision, occurred at an altitude of 9000-feet approximately 3-miles south of Destruction Island. Records do not report when this squadron departed NAAS Quillayute but it appears to have taken place around December 1944.

In early January, Squadron VC-3 arrived and began training within one day. Unlike prior squadrons, this group had combat experience and was composed mostly of men who had seen action in the South Pacific. The crews trained constantly due to a break in the inclement weather on Olympic Peninsula. The squadron was transferred to San Diego in March 1945. The station’s hosted its fourth squadron, composite squadron VC-78, beginning on April 8th. The squadron completed its assigned syllabus in a timely fashion as the weather was relatively hospitable during their month-long assignment. The group depart NAAS Quillayute on May 28th, 1945 (Dobbins 1945).

A contingent of officers and enlisted men from the Army Air Corps at Paine Field reported to NAAS Quillayute between May 4th to 11th. The group brought two P-38 lighting planes. On July 25, Pilot Ensign Lamar C. Fitzpatrick went missing during a routine gunnery hop. Restricted visibility caused by weather and eventual nightfall restricted a two-day search for the downed FM Wildcat. Search and rescue operations involved two LTA crafts from Tillamook and crash boats from Neah Bay, Grays Harbor, and Quillayute were deployed. All efforts were discontinued on July 27th. Squadron VC-82 departed the station on August 5, 1945 and was replaced by squadron VC-85 on August 6th.

While no land incursions were made during the course of the war, aircraft from the air station were reportedly involved in sinking of a submarine “three hundred yards northeast of Wada Island” (King 2005). According to Boyd Rupp, a State Patrol officer assigned to scout for Japanese espionage activities, “three Quillayute attack planes that were used for strategic bombing, with single engines, twice as big as a "Hell Cat," swooped over the tree line and each released a can the size of a barrel that exploded in the water three hundred yards northeast of Wada Island. This bombing was never publicized because it might have hurt the war effort.”

Blimps

The use of dirigibles or lighter-than-air craft at Quillayute remained limited in scope throughout much of its history. The nearest airships were housed at Tillamook, Oregon, which would deploy them to patrol the coast for enemy submarines. These blimps would use the station at Quillayute for touch and go or emergency lands. In January 1944, a blimp from Naval Air Station, Tillamook attempted an emergency landing due to inclement weather. After struggling to secure the blimp to the mooring mast, the K-39 Blimp was overtaken by heavy winds and crashed in a nearby timber stand approximately one mile north, destroying the blimp (Archibald 97).

Photo 13. Lighter-than-Air craft tethered to Mast. Source: Rod Fleck.

Later that month, the Commanding Officer of NAAS Quillayute and its Public Operation’s Officer were assigned to NAS Tillamook for temporary duty. This assignment was arranged in connection with lighter-than-air handling operations. Over the course of this assignment, the officers gained “considerable experience” in the landing of blimps (Dobbins 1945).

In April 1944, a blimp and two aircrews arrived from Tillamook for semi-permanent stationing at Quillayute. These LTA operations began with one blimp assigned two different flight crews and a Hedron (Headquarters Squadron) detachment was based at the station. On June 5th, a blimp was “destroyed by a crash” while on special assignment, searching for a lost plane of the Royal Canadian Air Force” out of British Columbia (pg. 20). The blimp was totally lost but its crew was able to escape. The destroyed vessel was replaced in July with another blimp, presumable from Tillamook. All dirigible activities closed for winter in October of that year.

In February 1945, high winds forced another blimp to make an emergency landing at the station. The LTA vessel was secured to the mooring mast, located on the north side of the airstrip, for two days until the storm cleared. On February 8th, the blimp returned to Tillamook, Oregon. On the 16th the blimp made two more landings and departures (Dobbins 1945).

Photo 14. Lighter-than-Air craft, ca. 1944.

Decommission

In January 1945, the Chief of Naval Operations appoint a Historical Officer to NAAS Quillayute. Lieutenant George A. Pettitt was tasked with capturing the history of the station from its initiation to December 1941. A report entitled History of Naval Auxiliary Air Station, Quillayute Washington and additional historical materials were submitted in September of 1945. With the announcement of the surrender of Japan, Station personnel were granted a two-day holiday between August 15th and 16th, 1945. Commissioned officers stayed aboard to execute all necessary duties while many off- duty men celebrated both in Forks and on the station. Within the month, plans to reduce the Station’s personnel, both enlisted and officers were under development. Officers from NAS, Seattle came aboard to inspect the handling of ordnance. Soon, many commissioned officers were transferred to other areas of the Navy to assist with other efforts.

The final squadron, VC-85, departed on September 22, 1945. Around the same time, Captains from Fleet Air Seattle came aboard to inspect the station to “evaluate its post-war possibilities.” By the end of the month, the station was placed on “caretaker status”. All buildings deemed nonessential to the caretaker operations were secured. Equipment no longer needed was shipped to other naval properties in accordance with NAC, Seattle’s direction.

An appraisal of the facility produced in 1947 reported that the station consisted of approximately 110-structures located on-site during the Navy’s tenure. Many of the buildings were declared surplus inventory by the War Assets Administration and were deemed non-essential to the continued operation of the facility as an airfield (King 2005). These structures were sold to private entities or other agencies are no longer extant.

Post-Military Use

The State of Washington acquired the property in 1962 for use as “an emergency landing field.” In 1997, the City of Fork began a correspondence with the Federal Aviation Administration and the Washington State Department of Transportation Aviation branch regarding thirty-three years of alleged mismanagement of the facility. This included neglect of maintenance, removal of structures, and mishandling of proceeds from the airport property. The City claimed that WSDOT has extracted a combined 1.5 million dollars from the property per timber harvest, gravel extraction, leasing agreements, and salvage of existing structures. Additionally, these proceeds were not used to improve the property but rather to fund other projects.

The final act of administrative malfeasance was WSDOT’s request to the Federal Aviation Administration to demolish five existing buildings on the property. The City of Forks believed that the continued decay of the airport, due to deferred maintenance by WSDOT, risked the future development of what was then known as the Quillayute State Airport. At the time, the City desired to rehabilitate the airport as part of a larger vision to make the facility “the region’s airport of the future” (Arbeiter 1997). In February 1997, negotiations began to transfer the airport from WSDOT-Aviation to the City of Fork (Brubaker 1997).

REFERENCES

Ames, Kenneth M., and Herbert D. G. Maschner. Peoples of the Northwest Coast, Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson Ltd., London. 1999

Arbeiter, Phil. “Correspondence with WSDOT Aviation re. FAA letter February 4, 1997.” City of Forks, Tab 3, Rod Fleck—Master Plan, February 14, 1997.

Archibald, Lonnie. Here on the Home Front: WWII In Clallam County. Olympus Multimedia, 2014

Banel, Feliks. “ All over the map: Neah Bay’s History Between Makah, Spanish, and British.”

Mynorthwest.com, April 12, 2019. Accessed January 2022. https://mynorthwest.com/1344432/neah-bay-name-history/

Bell-Walker Engineers, Inc. “Forks Municipal Airport, Airport Master Plan.” City of Forks, WA, May 1987.

Brubaker, Bill. “Re: Quillayute State Airport,” Correspondence with Phil Arbeiter, Mayor, Forks Washington, February 27, 1997.”

Carlson, Roy L., and Luke Dalla Bona (editors). Early Human Occupation in British Columbia.UBC Press, Vancouver, BC, 1996.

Denfeld Ph.D. , Duane Colt. “World War II: Civilian Airports Adapted for Military Use.” Historylink Essay No. 10110, August 21, 2012. Accessed January 2022.

https://www.historylink.org/File/10110

Dobbins, Lieut. USNR Robert N. “Monthly Report of Station Activities for War Diary.” Naval Auxiliary Air Station, Quillayute, Washington, NAAS14/A12-1, Serial, December 1943-October 1945.

Dobbins Sr., Captain Robert N. A Lifetime of Experiences. 1993

Forks Forum. “Quillayute Naval Auxiliary Air Station, (NAAS)/Quillayute State Airport. December 30, 2020. Accessed January 2022. https://www.forksforum.com/news/quillayute-navalauxiliary-air-station-naas-quillayute-stateairport#:~:text=The%201%2C202%2Dacre%20property%20was,station%20during%20World%20War%20II.

Fladmark, K. R. “An Introduction to the Prehistory of British Columbia.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 6:95-256, 1982.

Fleck, Rod. Personnel communication with Stephen Austin, City of Forks, Washington, January 2022.

Grant, David, Colt Denfeld, and Randal Schalk. “US Navy Shipwrecks and Submerged Naval Aircraft in Washington: An Overview.” International Archaeological Research Institute Inc., Seattle, Washington, December 1996. Accessed January 2022.

https://www.denix.osd.mil/cr/archives/archaeology/archaeology-underwater-archaeologyarchives/report17/71_U.S.%20Navy%20Shipwrecks%20and%20Submerged%20Naval%20Aircraft%20in%20Washington.pdf

Greengo, Robert E. and Robert Houston. Excavations at the Marymoor Site. Magic Machine, Seattle, Washington, 1970.

Guzman, Gonzalo with Walt Crowley. “Mexican and Spanish settlers complete Neah Bay Settlement in May 1792.” Historylink Essay # 7953, September 20, 2006. Accessed January 2022. https://www.historylink.org/file/7953

Halloin, Louis J. “Soil Survey of Clallam County Area, Washington.” 1987. Accessed January 2022. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_MANUSCRIPTS/washington/WA609/0/wa609text.pdf, accessed June 20, 2016.

King, Cathy. “World War II on the West End.” The University of Washington. The Pacific Northwest: Olympic Peninsula Community Museum, Online Exhibits, August 2005. Accessed January 2022. https://content.lib.washington.edu/cmpweb/index.html

Kruckeberg, Arthur R. The Natural History of Puget Sound Country. University of Washington Press. Seattle, September 1995.

Magnuson, Andrew Craig. “Spruce Production Division: Railroad No. 1.” Forks, Washington, April 14, 2007. Accessed January 2022. http://www.craigmagnuson.com/spdrr01.htm Naval History and Heritage Command. “Composite Squadron Ninety-six (VC-96).” NH Series, 80-G-3690000, 80-G-369612, April 24, 1945. Accessed January 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhcseries/nh-series/80-G-369000/80-G-369612.html

Matson, R. G. and G. C. Coupland. The Prehistory of the Northwest Coast. Academic Press, San Diego, California, 1995.

Moss, Madonna. Northwest Coast: Archaeology as Deep History. Society of American Archaeology Press. Washington, D.C., 2011.

Larson, L. L., and D. Lewarch (editors). The Archaeology of West Point, Seattle, Washington: 4,000 years of Hunter-Fisher-Gatherer Land Use in Southern Puget Sound. On file at the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Olympia, 1995.

Nelson, C. M. Prehistory of the Puget Sound Region. In Northwest Coast, edited by Wayne P. Suttles pp. 481-484. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 7, W.C. Sturtevant, general editor, Smithsonian Institute, Washington D.C. 1990.

Pelt, Julie Van. “Forks—Thumbnail History.” Historylink Essay No. 8397, December 10, 2007. Accessed January 2022. https://www.historylink.org/file/8397

Pettitt, Lieut. George A. “History of Naval Auxiliary Air Station, Quillayute, Washington.” United States Navy, Commanding Officer, N.A.A.S, Quillayute, Historical Officer, Declassified, Aviation Circular Letter #74-44, 1945.

Pettitt, George A. “The Quileute of La Push: 1775-1945.”Anthropological Records, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960. Accessed November 2021, https://archive.org/details/quileuteoflapush0014pett/page/n3/mode/2up

Powell, Jay and Vickie Jensen. Quileute: An Introduction to the Indians of La Push. University of Washington Press, January 1976.

Powell, Jay, and Chris Morgenroth III. “Quileute Use of Trees & Plants: A Quileute Ethnobotany” Submitted to the Quileute Natural Resources, 1998.

Sanchez, Antonio. “Bruno de Hezeta (Heceta) party lands on Future Washsington Coast and Claims the Pacific Northwest for Spain on July 12, 1775.” Historylink Essay # 5690, April 22, 2004. Accessed January 2022. https://www.historylink.org/File/5690

Silva, Victor. “Ghost Blimp Mystery of WWII—Crashed in San Francisco & Crew Was Never Found.” War History Online.com, History, Instant Articles, World War II, October 3, 2018. Accessed January 2022. https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/missing-crew-of-thel-8-ghost.html

Tait, Captain George F., C.E. et al. “Report of Air Corps Site Selection Board on Quillayute Air Field, Clallam County.” United States Army Washington. May 12, 1942.

Tonsfeldt, Ward 2005 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for U.S. Army Spruce Production Division Railroad #1. August 5, 2005 United States Navy. “History of NAAS Quillayute.” Declassified: Confidential, Lieutenant Commander Robert N. Dobbins, Commanding Officer, pp.

XI-Feb 29, 1944.

Unknown. “Declassified history of Naval Auxiliary Air Station.” Part one, precommissioning period, Quillayute, Washington. [Washington, D.C.?] : [U.S. Navy?], [2006?] spruce for the air fir for the sea 1918. https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/pioneerlife/id/9385/rec/5

University of Washington, University Libraries. Quillayute Naval Auxiliary Air Station. https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/search/searchterm/Quillayute%20Naval%20Auxiliary%20Air%20Station/field/all/mode/all/conn/and/cosuppress/

Van Pelt, Julie. “Forks—Thumbnail History.” Historylink Essay # 8397, December 10, 2007. Accessed January 2022. https://www.historylink.org/file/8397

(From City of Forks Quillayute Airport Master Plan, Drayton Archeology Report, pgs. 194 to 221) https://qa4cr.org/city-forks-quillayute-airport-master-plan

Publish date